Third law of thermodynamics

| Thermodynamics | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The third law of thermodynamics is a statistical law of nature regarding entropy and the impossibility of reaching absolute zero of temperature. The most common enunciation of the third law of thermodynamics is:

| “ | As a system approaches absolute zero, all processes cease and the entropy of the system approaches a minimum value. | ” |

Note that the minimum value is not necessarily zero,[1] although it is almost[2] always zero in a perfect, pure crystal; see the article on residual entropy for more information.

(As always, reducing the entropy of a system requires increasing the entropy of its surroundings, in accord with the second law.)

Contents |

History

The third law was developed by the chemist Walther Nernst, during the years 1906-1912, and is thus sometimes referred to as Nernst's theorem or Nernst's postulate. The third law of thermodynamics states that the entropy of a system at absolute zero is a well-defined constant. This is because a system at zero temperature exists in its ground state, so that its entropy is determined only by the degeneracy of the ground state; or, it states that "it is impossible by any procedure, no matter how idealised, to reduce any system to the absolute zero of temperature in a finite number of operations".

An alternative version of the third law of thermodynamics as stated by Gilbert N. Lewis and Merle Randall in 1923:

| “ | If the entropy of each element in some (perfect) crystalline state be taken as zero at the absolute zero of temperature, every substance has a finite positive entropy; but at the absolute zero of temperature the entropy may become zero, and does so become in the case of perfect crystalline substances. | ” |

This version states not only ΔS will reach zero at 0 kelvins, but S itself will also reach zero, at least for perfect crystalline substances. (This statement is now known to have some rare exceptions.)[2]

Overview

In simple terms, the Third Law states that the entropy of most pure substances approaches zero as the absolute temperature approaches zero. This law provides an absolute reference point for the determination of entropy. The entropy determined relative to this point is the absolute entropy.

A special case of this is systems with a unique ground state, such as most crystal lattices. The entropy of a perfect crystal lattice as defined by Nernst's theorem is zero (if its ground state is singular and unique, whereby log(1) = 0). An example of a system which does not have a unique ground state is one containing half-integer spins, for which time-reversal symmetry gives two degenerate ground states. Of course, this entropy is generally considered to be negligible on a macroscopic scale. Additionally, other exotic systems are known that exhibit geometrical frustration, where the structure of the crystal lattice prevents the emergence of a unique ground state.

Real crystals with frozen defects obey this same law, so long as one considers a particular defect configuration to be fixed. The defects would not be present in thermal equilibrium, so if one considers a collection of different possible defects, the collection would have some entropy, but not actually have a temperature. Such considerations become more interesting and problematic in considering various forms of glass, since glasses have large collections of nearly degenerate states, in which they become trapped out of equilibrium.

Another application of the third law is with respect to the magnetic moments of a material. Paramagnetic materials (moments random) will order as T approaches 0 K. They may order in a ferromagnetic sense, with all moments parallel to each other, or they may order in an antiferromagnetic sense, with all neighboring pairs of moments antiparallel to each other. (A third possibility is spin glass, where there is residual entropy.)

Yet another application of the third law is the fact that at 0 K no solid solutions should exist. Phases in equilibrium at 0 K should either be pure elements or atomically ordered phases.[3]

Mathematical Evaluation of the third law of thermodynamics

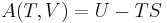

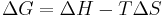

In an isothermal process

.

.

At  the entropy

the entropy  vanishes. The changes in the Gibbs potential and in the enthalpy are equal (

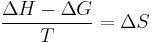

vanishes. The changes in the Gibbs potential and in the enthalpy are equal ( certainly being bounded). But that is not sufficient to explain why they remain approximately equal over some non-negligible temperature range. However , dividing

certainly being bounded). But that is not sufficient to explain why they remain approximately equal over some non-negligible temperature range. However , dividing  on both sides

on both sides

.

.

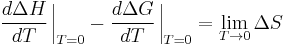

From the above equation  at

at

The left-hand side of equation is an indeterminate form as  . The limiting value is obtained as per the law by differentiating numerator and denominator separately (l'Hôpital's rule), whence

. The limiting value is obtained as per the law by differentiating numerator and denominator separately (l'Hôpital's rule), whence

Finally

Since  and

and  have the same slope at

have the same slope at  .

.

See also

- Adiabatic process

- Ground state

- Laws of thermodynamics

- Residual entropy

- Thermodynamic entropy

- Timeline of thermodynamics, statistical mechanics, and random processes

References

- ↑ Kittel and Kroemer, Thermal Physics (2nd ed.), page 49.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 See Ice Ih#Proton disorder for an example of a perfect, pure crystal in which it is believed that there is residual entropy

- ↑ Abriata, J. P.; Laughlin, D. E. (2004). "The Third Law of Thermodynamics and low temperature phase stability". Progress in Materials Science 49 (3–4): 367–387. doi:10.1016/S0079-6425(03)00030-6.

Further reading

- Goldstein, Martin & Inge F. (1993) The Refrigerator and the Universe. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674753240. Chpt. 14 is a nontechnical discussion of the Third Law, one including the requisite elementary quantum mechanics.